How the U.S. Met the Beatles

Fri Jan 30, 2004

LOS ANGELES/LONDON (Billboard)

![]() n late 1963, Alan Livingston, then-president of Capitol Records, brought home a single by a newly signed act and played it for his wife, Nancy.

n late 1963, Alan Livingston, then-president of Capitol Records, brought home a single by a newly signed act and played it for his wife, Nancy.

"I had great respect for her, because she had a good ear," Livingston recalls. "She looked at me and said, "'I want to hold your hand?" Are you kidding?' I said, 'God, maybe I made a mistake!"'

The Beatles were by no means a commercial slam-dunk.

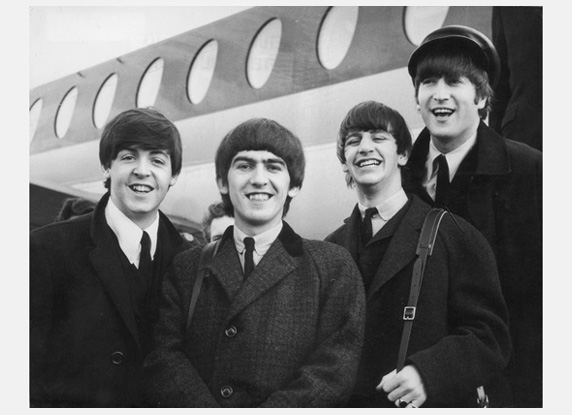

Yet the group's "invasion" was met with an unprecedented wave of fan and media frenzy that stunned almost everyone, including the Fab Four.

Today, the best-known TV journalist of the '60s is still baffled by the explosion.

"I remained, and remain today, dumbfounded at that kind of hysterical reaction to this music," says Walter Cronkite, the former "CBS Evening News" anchor, who reported the onset of Beatlemania.

What is certain is that the event launched the modern era of popular music. During their relatively short career -- the Beatles broke up in 1970 -- the group set standards by which almost every other rock group has been measured.

Now, on the 40th anniversary of the Beatles' landing in New York on Feb. 7, 1964, it's easy to forget that hardly anyone in the U.S. knew what a Beatle was only weeks before their arrival.

"Christmas of 1963, the Beatles are virtually unknown in America," says Bruce Spizer, author of the comprehensive new book The Beatles Are Coming! The Birth of Beatlemania in America (498 Productions).

"The next thing you know, six weeks later, 73 million people are watching them on The Ed Sullivan Show. It's just phenomenal how quick it happened."

FROM FLOP TO SMASH

It seems unbelievable today, but Capitol's signing of the Beatles was not announced until Dec. 4, 1963 -- a mere two months before the group's Feb. 9, 1964, U.S. TV debut on Ed Sullivan's CBS show.

Capitol had right of first refusal on the Beatles in the U.S.; EMI, its major stockholder, released the group's music in the U.K. on its Parlophone imprint.

Despite the Beatles' run of hits in England, Capitol repeatedly passed on the band. Livingston had sought the advice of Dave Dexter, Capitol's international A&R rep.

"He said, 'Alan, forget it,"' Livingston recalls. "'They're a bunch of long-haired kids. They're nothing.' I said, 'OK,' and I had no reason to be concerned, because nothing from England was selling here."

EMI had licensed some of the Beatles' singles to U.S. indies Vee Jay and Swan. All of them flopped; the biggest, "From Me to You," had peaked at No. 116 on the Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 chart in August 1963.

But the Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, persevered. Tony Barrow, Epstein's U.K. press officer, remembers, "He realized that big money was in America."

In November 1963, Epstein persuaded Sullivan, host of the top-rated U.S. variety show of the day, to book the Beatles. Armed with that commitment, he convinced Livingston to sign the group and lay out $40,000 to promote the first Capitol single, "I Want to Hold Your Hand."

The single was scheduled for a Jan. 13, 1964, release. But events altered Capitol's game plan.

"The whole thing that broke the Beatles was just one of those quirks where things fell into place," author Spizer says. "You couldn't have written the script if you had tried."

Spizer says "the first domino fell" Dec. 10, 1963, when The CBS Evening News aired a story by U.K. correspondent Alexander Kendrick about the excitement the Beatles were generating in England. An abbreviated version of the report had been telecast on the CBS morning news show Nov. 22, the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Cronkite decided to air the complete story in early December.

Cronkite recalls, "In the wake of the assassination story, nothing else was happening in the world, at least in the United States -- stuff that was important, that is. So we actually had an opportunity to use it.

"I was not entirely thrilled with it myself, to tell you the truth," he adds. "It was not a musical phenomenon to me. The phenomenon was a social one, of these rather tawdry-looking guys, we thought at the time, with their long hair and this crazy singing of theirs, this meaningless 'wah-wah-wah, wee-wee-wee' stuff they were doing."

One viewer of the broadcast, however -- a 15-year-old Silver Spring, Md., girl named Marsha Albert -- had a different point of view.

"She liked what she saw and heard," Spizer says, "and wrote a letter to her radio station, WWDC, referring to the broadcast and saying how great it was, and why can't we have music like that in America.

"Carroll James, who was a DJ with WWDC, obtained the British 45 of 'I Want to Hold Your Hand' and aired it on Dec. 17 and got immediate favorable response in the Washington area."

Jocks in Chicago and St. Louis quickly procured copies of "I Want to Hold Your Hand" from James and began spinning them heavily.

RADIO PLAY

Alarmed by the early airplay on its as-yet-unreleased single, Capitol initially sought a cease-and-desist order.

But, Beatles authority Martin Lewis says, " said, 'Hold on a moment. We spend all our lives hustling DJs to play our records. Now we're threatening to sue 'em. This is insane. Maybe we should change our plans.' And they hustled up the release."

Capitol moved the single's release date to Dec. 26 -- an unusual act of timing that paid off.

High schools were still on Christmas break. Lewis says, "Kids who normally would have heard the record only in the early morning or late evening when they got home from school are hearing it all the way through the daytime...In that period, the kids go wild, and it takes off on its own volition."

"I Want to Hold Your Hand" entered the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 45 on Jan. 18, 1964, and hit No. 1 a mere two weeks later, on Feb. 1.

In New York, pandemonium ensued. Thousands of shrieking teens mobbed Kennedy International Airport when the Beatles arrived Feb. 7 on Pan Am flight 101 from London. Thousands more laid siege to the Plaza Hotel, where the group was staying.

"There was bedlam at 59th and Fifth Avenue," Livingston says. "Nobody could move, the traffic was so held up. It was practically a riot scene. The hotel said to me, 'Don't ever book those boys in here again."' ![]()

|

|

|